Volume 1 Number 1

Global Nurse |

| The Journal of Nurses Reaching Out Published quarterly |

| Volume 1 Number | Spring 2015 |

| Editorial – Michelle Grainger | Page 3-4 |

| Regulars | |

| The Column | Page 5 -7 |

| Thought for the Season | Page 8 -10 |

| Features | |

| Globalisation of palliative care | Page 11-15 |

| The Ugandan Health Care system: | Page 16 -20 |

| Children’s Mental health problems following conflict | Page 21-27 |

| Student Nurse’s reflections | Page 28 -30 |

| Elective Placement : A Learning Opportunity | Page 31-32 |

| Guidelines for authors | Page 33-35 |

| Writing a case study for Global Nurse – the guidelines | Page 36 |

| Gulu Regional Referral Hospital | Page 37 |

| A Poem of Hope | Page 38 |

| Page 1 |

| Editor in Chief Michelle Grainger Chief Sub-editor Roger Skelhorn Sub-editor Charlotte Grierson |

| Contact us at: globalnurse@nursesreachingout.org |

| Editorial Board Mariam S. Awad, Dean of Nursing and Health Sciences, Bethlehem University Dr Jeff Evans, Independent Anthropologist, North Wales Vincent Mujune, Public Health Consultant, Uganda Prof. Emmanuel Moro, Dean, Faculty of Medicine, Gulu University, Uganda Marian Surgenor, Head of Global Health, University Hospital South Manchester Dr. Brian Nyatanga, Senior Lecturer, Applied Professional Studies, University of Worcester Dr. Sharon Frood Director of the GoGo Trust, UK Dr. Zainab Zahran, Lecturer, Kings College London |

| Page 2 |

| Editorial – Michelle Grainger |

| Page 3 |

| The editors would welcome contributions which cover all sorts of health and nursing topics global issues, political comments and erudite opinions. In addition we want to encourage case studies which not only examine individual patients stories, but cover groups and special collectives in health care. There will also be room for research papers and special clinical features on medical and surgical conditions. It is also intended to include spiritual issues and beliefs which affect nursing and medical care. We further intend to keep workers up to date with tasks, skills and procedures which are vital to evidence based care and the comfort of patients. Global Nurse will remain free to nurses and healthcare workers who are working in developing countries. We would like to thank Student nurse Beth Ezebilo a student from Kingston University School of Nursing and Midwifery who came up with the title of the journal. Finally, many thanks to you, our future readers, for supporting us and we look forward to a successful time ahead. |

| Michelle Grainger, Senior Lecturer, Kingston and St. George’s University, London. |

|

| Page 4 |

| The Column – Ebola has not gone away |

| In his excellent short book on the subject of Ebola, Quammen (2014) urges us all to be, “prepared to act as global citizens in the face of what has become a global challenge.” There is no doubt that he makes a very valid and important point and as the subject disappears from the media headlines, it would be very foolish to become complacent about thinking that the disease or indeed the virus which causes the problem has been eradicated.

Ebola virus disease emerged in the mid seventies in parts of Central Africa particularly in the dense and scarcely populated areas of the Congo Forests. Quammen (2014) points out that the first recorded case was confirmed in 1976 when he came across it in a small village in the northeast of Gabon, near the border with the Congo. Eighteen people were affected in the village which was called Maryibout 2. They had been eating a butchered chimpanzee and became very ill and were taken to their local hospital some fifty miles away. All suffered a varying amount of symptoms from fever, headache, vomiting, bloodshot eyes, and bleeding. Those who cared for these patients also became infected and within a short period of time thirty-one people got sick of whom twenty-one died. A team of medical researchers which included a Paris-trained virologist identified and confirmed the disease was Ebola. Although chimps and gorillas have been found to be highly susceptible to Ebola it is thought that they are not the ‘reservoir host’ which originally helps the virus develop its potential harm to humans. Some other living creature is responsible for providing this ‘environment’. More recent suggestions have centred on Egyptian fruit bats which seem to fly long distances and keep closely together when resting in trees, caves and crevices. A pattern of outbreaks of Ebola virus disease has spread across Central Africa to South Sudan, and Gulu in Northern Uganda. The virus has been carried by humans on planes to South Africa and during the most recent outbreak to Lagos in Nigeria. Criss-crossing the continent of Africa it has recently caused major problems in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone in the West of Africa. All this activity has seen the virus changing and adapting itself, wherever it has been identified. It seems to be mutating prolifically and accumulating a fair degree of genetic variation as it is replicated within each human case. The recent West African virus is different to the earlier strain in the Congo. A problem with trying to find Ebola’s reservoir or what is harbouring the virus is the transitory nature of the disease in the human population. It seems to disappear for years at a time then suddenly it comes back and as the current outbreak has proved, more difficult to control. Many viral ecologists are spending their time searching for the virus in places where they have heard it is possibly hiding. These have included sites in forests, caves and areas where the death rate in animals such as chimps and gorillas has been abnormally high. |

| Page 5 |

| There has been an outbreak of an Ebola-like virus in imported monkeys at an animal research facility in the United States of America. This was reported by Preston (1994) when an animal research lab near Washington, DC. found a virus in monkeys which led to all the monkeys dying of a bleeding disorder.

Some were put down and the environment treated by a special military unit responsible for dealing with chemical and biological weapons. It is perhaps reassuring that there are governmental agencies and scientists willing to work and study this area of human threat. It was also felt at the time that the disease might be spreading by airborne droplets. So far however there has been no evidence that Ebola is transferred in the air and the current scientific evidence is that it is transferred by touch. The Ebola virus is contained in the person’s body fluids such as the blood, saliva, and sweat. The carer of the Ebola patient must not touch the person, kiss, cuddle, have sex, share food or needles with them. The patient’s blood faeces and vomit are dangerous and should be disposed of carefully. Care of the eyes, nose, mouth and ears should be carried out using gloves and special body protection for the carer. Ebola nursing carries a high risk of cross infection if the appropriate barrier nursing techniques are not observed including changing clothing carefully and following strict washing and cleansing with bleach type agents. No one is allowed to nurse patients with Ebola if they have any minor cuts or abrasions to their skin. Recently those health care teams who have gone out and helped in the current crises have been screened and specially trained for the job. Recently however I did have a chance to talk to an African nurse who helped out in one of the biggest outbreaks prior to this latest one. She told me that they were lucky because, the doctor who first detected that a new patient may have the disease; instructed them to carry out very strict barrier nursing. They used face masks, gowns, and rubber boots and were meticulous in cleaning everything with Harpic, which is a strong bleaching agent. The first signs and symptoms of the disease occur within 2-21 days or 8 to 10 days on average. They are often: high fever, headache, joint and muscle pain, sore throat and intense muscle weakness. These early symptoms can be confused with such illnesses as flu, typhoid, and malaria, which of course are very common in parts of Africa. Later symptoms include diarrhoea, vomiting, a rash, stomach pain, impaired kidney and liver function. Bleeding internally may follow resulting in bruising, and bleeding from the mouth, nose and ears. Blood may also occur in the vomit, faeces, urine and from the vagina. It has been reported that patients also get red eyes. There is of course a very high mortality rate and successful treatment and recovery is possible but as we have seen in the latest outbreak still very low. As with many epidemics there also seems to be a few who survive the disease and develop the antibodies to the threat. |

| Page 6 |

| Page 7 |

| Thought for the season: Hope Michelle Grainger |

| Page 8 |

| Hopelessness on the other hand might be seen as leading to depression and an exacerbation in in their condition.

Hope is of course useful not just at the end of a patient’s life or when medical treatment has been completed or withdrawn. It is an invaluable concept throughout any patients recovery and rehabilitation. Groopman (2004) found that some people find hope despite facing severe illness, while others do not. Groopman’s experiences with patients led him to conclude that there was much to appreciate in the term,hope, for example, he found that he could define hope as, “the elevating feeling we experience when we see-in the mind’s eye-a path to a better future. Hope acknowledges the significant obstacles and deep pitfalls along that path. True hope has no room for delusion. Clear-eyed hope gives us the courage to confront our circumstances and the capacity to surmount them.” Groopman (2004) goes on to point out that for all his patients, ‘hope, true hope’, has proved as important as any medication he ever prescribed or any procedure he ever performed. There is a considerable amount of literature which exists contending that positive emotions affect the body in health and disease. Some of these accounts are very subjective and are vague, unsubstantiated and merely wishful thinking. Some writers depict hope as a magic wand in a fairy tale that will eventually miraculously restore the patient. Personal recorded experiences of suffering and pain can however give us an insight into what is the role of hope in recovery and chronic illness. For example a patient with severe back pain recorded in his recovery that through a series of circumstances he found that only hope could have made his recovery possible. Rekindled hope gave him the courage to embark on a new but difficult treatment program and the resilience to endure this process. Hope gave him the push needed to take a change and not give up. The result was a success not only on his psychology but also on his physical health. The person who wrote about the above experience was Groopman himself. He now believes that future studies will discover the, ‘energizing feelings’ of hope and how it can contribute to a patient’s recovery. Belief and expectation are the key elements of hope and can block pain by releasing the brains endorphins and enkephalins, mimicking the effects of morphine. There is further indications that hope can also have important effects on the physiological processes like respiration, circulation and motor function. Groopman believes that over the years of studying and searching for hope in his patients he has discovered that self insight and self control over ones circumstances are the key which hope brings to the patients recovery and coming to terms with their health problems. Hope is therefore more than a word it is an inner feeling at the very centre of healing. In the conclusion of his book Groopman (2004) states, “for those who have hope, it may help some to live longer, and it will help all to live better”. |

| Page 9 |

| Michelle Grainger, Senior Lecturer, Kingston and St. George’s University, London. |

| References

Groopman, Jerome (2004) The Anatomy of Hope. Random House. New York |

| Page 10 |

Globalisation of palliative care: addressing the challengesDr. Brian NyatangaIntroduction As an international palliative care community, it is even more important that we keep the palliative care agenda alive with our own governments and specific departments/ministries in our different countries and organisations like ‘nurses reaching out’ Uganda (http://www.nursesreachingout.org/). Such small organisations have advantages of being: While it may be clear that death is imminent, this does not exonerate governments from allocating funds and human resources to care for such patients. It is important to acknowledge the impact that any death has on families and friends. Now imagine the impact of a death that was poorly managed, where patients die in excruciating pain, suffering, emaciated and with no dignity, will have on bereaved families and close friends. |

| Page 11 |

| The argument should be made for the well being of the bereaved as well, since they are the ones who are left with images of poor care.

The challenges of providing palliative care First, the global network could not dictate to all these countries, to prioritise palliative care. What needs to happen in a subtle way is to create a global culture where palliative care is seen and believed to be a central requirement for all health care systems. This will also help to integrate pain management into the main stream health care system. The picture is slightly different when we think of palliative care globally; the main challenge for developing countries is the ever growing burden of patients presenting with HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS 2013) and the associated pain. For example, in sub-Saharan Africa, in addition to having 24.7million people living with HIV/AIDS, another 1.4 million new infections are reported per year on average (UNAIDS 2103). This is a worrying figure when compared to 700,000 new cancer diagnoses in Africa per year. Despite this, there is an increasing awareness of palliative care in developing countries, but more needs to be done to maintain the momentum through education, training and research. The burden of HIV/AIDS should not deter our efforts, but instead, increase our resolve to provide palliative care for all who need it regardless of diagnosis. The cycle of pain, anxiety and psychological distress needs breaking down, and a more logical argument is to treat the pain first, and hope that the other problems can be minimised or eliminated altogether. Health ministries in developing countries need to ensure drug (opioid) availability and proper use are encouraged as opposed to opiophobia related to addiction, which is often a misplaced myth that needs correcting through education. It is now clearly documented (Teunissen 2007) that pain and psychological distress are common in most patients living with cancer and HIV/AIDS. It is hardly surprising that such patients’ quality of life is always low, and therefore necessitating an integrated approach to relieve the distress in order to enhance their quality of life. Policy makers and politicians can help to review palliative care and see it as a priority, which means funding and the provision of services can also be improved. When funding is provided, it is possible to develop more educational programmes, either within countries or through exchange programmes with developed countries. Education has the benefit of changing minds and affecting attitudes. The suggestion here is not merely focusing on health care professionals alone, but to educate government ministers, managers and leaders in health care about the philosophy and practice of palliative care. Evidence based education has more impact on getting things done, so evidence about the spread of cancer and other diseases should be part of the education programme. Challenge v opportunity Although the above seem like challenges, there are also opportunities attached to developing countries in Africa. |

| Page 12 |

| Page 13 |

| While all the above efforts can help to improve the delivery of palliative care in developing countries and Africa in particular, we also have to address other fundamental issues inherent within the continent that have perpetuated the state of these countries as ‘developing’. While all the above efforts can help to improve the delivery of palliative care in developing countries and Africa in particular, we also have to address other fundamental issues inherent within the continent that have perpetuated the state of these countries as ‘developing’. Most developing countries have received donor aid, but somehow, this support has not resulted in development but a perpetual state of dependency. A close look suggests a lack of investment, and proper infrastructure that would support the economic development and prosperity of any nation.

The point to argue is that in developing countries, there needs to be systems and structures in place to nurture and guide the development of not only palliative care services, but the whole country’s health care infrastructure. One of the most destructive features found and not only in developing countries, but the world at large, is corruption, although the impact is felt more in developing countries. Where corruption strives, it is often associated with individual factors such as greed, and at government level, a sign of weak or failed governance. With failed governance comes lack of accountability, no monitoring processes, no shared vision about health care and the resources/wealth are only enjoyed by a minority in power or connected with those in power. This is important to understand as corruption has a negative impact on health and palliative care in particular: · Reduces the effectiveness and equity of health and palliative care services; It is important for developed countries to realise that in order for palliative care to thrive in developing countries, it is crucial that corruption is eradicated. While corruption is still rife, funds should not be given directly to governments, instead it should be given through investment in facilities, resources like education and training in-country. The next step might be to engage with Government officials heading ministries such as health in order to create transparency and accountability. Governments should demonstrate their commitments to sustainability by agreeing to continue with developments once the initial funding ends. Governments should involve all citizens regardless of political views, in decision-making and running of the country. It is important that all citizens benefit from the wealth of the country and be motivated to build a future they are proud to leave behind for their children. Without these fundamental improvements palliative care will only remain as an unfulfilled potential in these countries. The sad truth from this is that these countries will remain in this state of ‘developing’. |

| Page 14 |

| Dr. Brian Nyatanga, Senior Lecturer, Applied Professional Studies, University of Worcester |

| References

Nyatanga, B. (2011) Reaching Out: doing ‘good’ in the name of palliative care. International Journal of Palliative Nursing 2011, Vol 17, No 6 |

| Page 15 |

| THE HEALTH CARE SYSTEM IN UGANDA: THE PLIGHT OF FRONTLINE HEALTH CARE PROVIDERS IN ENSURING QUALITY OF CARE Dr. Moro Emmanuel Ben, Piloyo Joyce Lilly Okot, Ocitti Aiello Beatrice 1.0 Introduction The National Population and Household census 2014 puts Uganda’s population at 34,856,813 people with a male/female ratio of 1:1.6, a crude birth rate of 42.1 and fertility rate of 6.2 and 82 percent of the population lives in rural areas (WHO, 2013). Economic indicators for 2013 show a GDP of 58,865 Ugandan Shillings (shs), Per Capita GDP at 1,638,939 shs and a Growth rate of 4.7% (Gormley & McCaffery, 2013). Major health indicators show Infant Mortality Rate = 54, Maternal Mortality Rate = 438, Contraceptive Prevalence Rate 30 and HIV Prevalence Rate of 7.3. The top five causes of death include: HIV/AIDS 20%, Malaria 12%, Lower respiratory tract infections 12%, Diarrheal diseases 9% and Perinatal conditions 4%. (Kaija and Okwiira Okwi (2003); Bakeera et al, (2009); (Gormley & McCaffery, 2013). This article gives a brief overview of the Health Care System in Uganda, how it works and who the role-players are in health care service delivery. The quality of health care at primary health care facilities is examined with special focus on factors influencing quality of care and how these impact on health care. 2.0. The National Health Care System 2.1. The Central System |

| Page 16 |

| Page 17 |

| 3.1. Effectiveness Effective care is care that is evidence based and can result into improved health outcome. There is little evidence that primary care is evidence-based and responds well to the expectations of communities (Kavuma, 2009; WHO 2013). 3.2. Efficiency Efficiency entails maximizing use of resources in health care delivery and avoiding waste. Various studies have shown that resource inputs of human resource, equipment, medicines and other health supplies in Uganda are inadequate (WHO, 2006; Chandler et al, 2013). 3.3. Accessibility This involves easy availability, timely delivery with good levels of competencies and resource inputs. 75 percent of households in Uganda live within 5 kilometers of a health facility; however, provider competencies, promptness of services and resource inputs are often questionable (UNHCO, 2012; WHO 2015). 3.4. Acceptability of Services Communities accept health care services that are responsive to their needs, culture and expectations. Communities in Uganda have very often complained of long waiting hours, harsh treatment, stigmatization and non-availability of health workers (MOH, 2009). Equity This is the delivery of health care without discrimination of gender, race, religion and socio-economic status. Basic health care is free to all Ugandans in public health facilities. There has however, been reports of preferential treatment for gender and socio-economic status (ACODE, 2010). Safety Safe health care delivery means minimizing any risks or harm to service users and providers. Safety is ensured through safe environment for service delivery and due diligence and indulgence of service providers (WHO, 2013). 4.0. The Plight of Frontline Health Care Providers Other challenges in the health system include: understaffing, low pay, dilapidated infrastructure, lacking or poor staff accommodation, shortage of medicines, supplies and equipment and lacking or poor supervision. The effects of these challenges have considerable toll on the health system, health care providers and the quality of care. |

| Page 18 |

| Conclusion Uganda has a well-designed Health Care System. The functionality of this system presents many challenges to health service providers and health service consumers especially at primary care levels. Precise study, analysis and mitigation of these challenges have not been forthcoming. Continued irresolution of these challenges has resulted in demotivation, low morale and burnout amongst frontline health care providers, dissatisfaction amongst health service consumers and questionable quality of health care. Dr. Moro Emmanuel Ben1, Associate Professor of Surgery, Gulu University Piloyo Joyce Lilly Okot2, Principal Nursing Officer, Gulu Regional Referral Hospital Ocitti Akello Beatrice3 , Senior Nursing officer, Gulu University References Bakeera, Solome K. et al, (2009) Community Perceptions and Factors Influencing Utilization of Health Services in Uganda. International Journal for Equity in Health.http://www.equityhealthj.com/content/8/1/25 Chandler, Clare I R et al (2013). Aspiring for Quality of Care in Uganda: How do we get there? http://www.human-resources-health.com/content/11/1/13 Kaija, Darlison and Okwiira Okwi, Paul (2003). Quality and Demand for Health Care in Rural Uganda: Evidence from 2002/2003 Household Survey.http://www.csae.ox.ac.uk/conferences/2007-edia-lawbidc/papers/428-kaija.pdf. Matsiko, Charles Wycliffe (2003). A Review of Human Resource for Health in Uganda. Human Resource Development Division, Ministry of Health and the Institute of Public Health, Makerere University. UMU Press 2003. MOH (2009), the National Health Care Policy: Reducing Poverty through Promoting Peoples’ Health. http://www.health.go.ug/National_Health.pdf. MOH (2010) Health Sector Strategic and Investment Plan (HSSIP) 2010/11 – 2014/15: Promoting People’s Health to Enhance Socio-economic Development. www.health.go.ug Mwebaza, Enid (2013). Overview of Nursing Services in Uganda. Uganda – UK Alliance.http://www.zuhwa.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/Uganda-UK-Alliance-Nurses-Presentation.ppt Smith, Duncan (2008). Nursing in Uganda: View from the Frontline.http://www.nursingtimes.net/nursing-in-uganda-view-from-the-frontline/445401.article |

| Page 19 |

| Ssekika, Edward (2013). Who will Heal Uganda’s Ailing Health System? http://observer.ug/features-sp-2084439083/57-feature/26662-who-will-heal-ugandas-ailing-health-system WHO ( 2015). 3rd Global Forum on Human Resources for Health: Human Resource Commitment Pathways Uganda.http://www.who.int/workforcealliance/forum/2013/hrh_commitments/en/Uganda Bureau of Standards (2014). National Population and Housing Census 2014. http://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic/sources/census/2010_PHC/Uganda/UGA-2014-11.pdf. UNHCO (2012). Client Satisfaction with Health Services in Uganda: A Citizen’s Report Card on Selected Public Health Facilities in Bushenyi and Lira Districts.http://unhco.or.ug/wpcontent/uploads/downloads/2013/05/CRC_UNHCO_HEPS_TAP_Final_Report_2012.pdf. WHO (2006). Quality of Care: A Process for Making Strategic Choices in Health Systems. http://www.who.int/management/quality/assurance/QualityCare_B.Def.pdf. WHO (2013). The WHO Nurses and Midwives Progress Report 2008 – 2012. WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data. http://www.who.int/hrh/nursing_midwifery/progress_report/en/. |

| Page 20 |

Determine prevalence of symptoms for mental ill health among orphans and vulnerable youth in Northern Uganda 2011-2013Vincent Mujune; Christina Ntulo; Patience Koburunga Affiliations: Conducted for BasicNeeds Foundation Uganda with financial support from UKAid Introduction |

| Page 21 |

| Other studies reported prevalence of PTSD and depression in post conflict communities at between 54 to 74.3% and 44% to 67% respectively Vinck et al., (2007), Roberts et al., (2008); and Bolton et al, (2007). In previous studies, more than 90% of adolescents reported exposure to severe trauma. Non-abducted adolescents reported more past suicidality (p=0.004, χ2=8.2) than adolescents who were abducted (MacMullin & Loughry, 2004).

In Amuru, Nwoya and Oyam districts were known for high HIV/AIDS prevalence among Orphans and Vulnerable Youth (9.1% prevalence in Amuru), poverty (68% live below the poverty line), insecurity, death and displacement of parents. Majority of them are poor, disowned by their families, and bear the brunt of stigma for the children born in captivity. All these youth are vulnerable to mental health problems (Northern Uganda prevalence rates for PTSD are between 54% and 74.3% and suicide rates are between 15/100,000 and 20/100,000). In the absence of research evidence to confirm the prevalence of symptoms for mental ill health among orphans and vulnerable youth (OVYs) in any post conflict community and the resultant effect it poses to functioning and participation in development among OVYs, a longitudinal study (2011-2013) was undertaken to study trends of prevalent symptoms of mental ill health among OVYs in Northern Uganda to inform the Victims to Victors programme about potential effect that changes in trends of prevalent symptoms for mental ill health pose on programme success. Method |

| Page 22 |

|

Prevalence = Population with symptoms x 100 Population of OVYs |

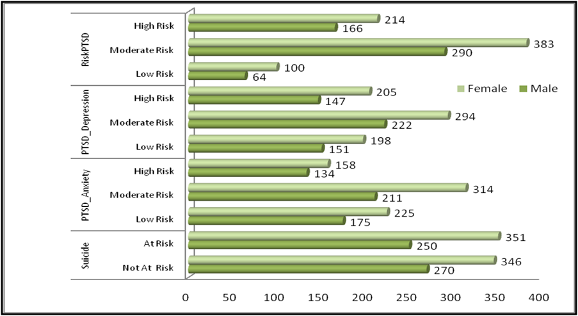

| The associations were measured using Pearson’s Chi square using SPSS statistical software packages. The statistical strength of relationships in the hypothesis were interpreted using the criteria below: P > 0.10: No evidence against the null hypothesis. The data appear to be consistent with the null hypothesis 0.05 < P < 0.10: Weak evidence against the null hypothesis in favor of the alternative 0.01 < P < 0.05: Moderate evidence against the null hypothesis in favor of the alternative 0.001 < P < 0.01: Strong evidence against the null hypothesis in favor of the alternative P < 0.001: Very strong evidence against the null hypothesis in favor of the alternative Discussion of study results Symptoms of PTSD with Anxiety were particularly high among 24% (n=292) while the overall prevalence of symptoms of PTSD_ Anxiety were significant among 67% (N=1218) OVYs. PTSD with Depression was high among 29% (n=352) OVYs and beyond moderate for 71.3% (N=1218) OVYs in the 3 districts. Although the prevalence rates for PTSD_Anxiety and PTSD_Depression were significant among OVYs, epidemiological studies for communities affected by the war in Afghanistan found high prevalence of symptoms of depression 68%, anxiety 72% and PTSD 42% (Cardozo et al. 2004, Scholte et al. 2004). For a significantly young and inexperienced population of OVYs, prevalence levels to that tune have the potential to increase their vulnerability and reduce their capacity to effectively participate in development opportunities within their community. Baingana. F et al, (2005) states that although not every individual will suffer from serious mental illness requiring acute psychiatric care, Mollica (2001) posits that the vast majority will experience “low-grade but long-lasting problems”. |

| Page 23 |

| Page 24 |

| Therefore, since all the highlighted forms of adversity were experienced by scores of the OVYs, it suffices to confirm that early childhood adversities such as not growing up with both parents, episodes of food insecurity among others had a predisposing effect of suicidal tendencies among OVYs.

Symptoms of mental ill health on functioning: There is a high potential for internalizing symptoms to affect physical and psychosocial functioning of the affected persons. I.e. 48% (n=528) OVYs had less interest in their hobbies and friends, 49% (n=593) OVYs felt cut off from other people, 57% (n=692) their feelings were less than before, 58% (n=710) felt their life shortened i.e. living in anticipation of death sooner than others, 69% (n=845) easily turned moody and angry, 64% (n=777) had trouble paying attention, 33% (n=407) thought of killing themselves, 29.4% (n=359) intentions to hurt themselves and 46.3% (n=565) felt they were better off dead i.e. wished for dead. The collective impact of these internalizing mental health problems on the individual have the potential to significantly affect their normal functioning. World Bank, (2003) identified links between mental ill health and psychosocial suffering and dysfunction. This dysfunction persists over time and is linked to decreased productivity, poor nutritional, health and educational outcomes, and decreased ability to participate and benefit from development efforts. Cognizant of the high prevalence of symptoms of mental ill health among OVYs implies that, strategies for youth empowerment in post conflict communities are integrated with mental health care; psychological and psychosocial interventions to break barriers to effective functioning and participation in development opportunities. Because psychological functioning and effective participation depend on ones state of psychological, spiritual and emotional wellbeing. Conclusions Acknowledgements: Local Government Administration of Amuru, Nwoya and Oyam districts, OVY beneficiaries of the Victims to Victors project in Amuru, Nwoya and Oyam districts, Dr. Okello James – Gulu University, Ms. Patience Koburunga M&E Officer BNFU, Ms. Janet Aloyo – Interpreter / Field Officer BNFU |

| Page 25 |

| Appendices: Figure: Number of OVYs and level of risk to conditions for mental ill health  Authors: Vincent Mujune, Consultant, Uganda, Christina Ntulo, Patience Koburunga 1. Chris Blattman & Jeannie Annan, 2008, Child Combatants in Northern Uganda: Reintegration Myths and Realities (2008), http://chrisblattman.com/projects/sway/ 2. Chris Dolan, 2002, which children count? The politics of children’s rights in Northern Uganda, Accord, http://www.c-r.org/our-work/accord/northern-uganda/which-children-count.php#text5 3. Erin Baines, Eric Stover, and Marieke Weird, 2006, WAR-AFFECTED CHILDREN AND YOUTH IN NORTHERN UGANDA: Toward a Brighter Future, http://www.macfound.org/atf/cf/%7BB0386CE3-8B29-4162-8098-E466FB856794%7D/UGANDA_REPORT.PDF 4. James Abola, 2011, The Youth Entrepreneurship Fund A headache or a cure? The monitor newspaper, 2011 http://allafrica.com/stories/201108310266.html 29.08.11 downloaded 22.09.11 5. Kasirye Victor, (2005), Uganda: The Pearl of Africa, Sacramento California: http://www.worldharvestmission.org/Uganda_Report.pdf 6. Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development, (2010), Millennium Development Goals Report for Uganda 2010; Accelerating progress towards improving maternal health, Kampala: 7. The National Development Plan, 2010 8. National youth council http://nycuganda.org/ 9. National Youth Council Act of 2003 10. National youth policy 11. Okello Lucima, 2002, Protracted conflict, elusive peace: Initiatives to end the violence in northern Uganda, Accord, http://www.c-r.org/our-work/accord/northern-uganda/contents.php |

| Page 26 |

| 12. 2Peace Recovery and Development Plan for Northern Uganda, Government of Uganda. 13. Suarez C. and E. St. Jean, 2005, A Generation at Risk: Acholi Youth in Northern Uganda, Liu Institute for Global Issues Survey of War Affected Youth (SWAY) reports SWAY is a research program in northern Uganda dedicated to understanding the scale and nature of war violence, the effects of war on youth, and the evaluation of programs to recover, reintegrate, and develop after conflict SWAY’s principal researchers are Jeannie Annan, Chris Blattman, Khristopher Carlson, and Dyan Mazurana. · SWAY I: The State of Youth in northern Uganda (2007) · SWAY II: The State of Female Youth in Northern Uganda (2008) · A Way Forward for Assisting Women and Girls in Northern Uganda (2008) · Making reintegration work for youth in northern Uganda (2007) · The psychosocial resilience of war-affected men (2006) |

| Page 27 |

| A student nurse’s reflection on how to prepare and get the most out of your placement – Katrina Sealey |

| Page 28 |

| It is up to you as the student to take charge of your own learning. Always discuss your ideas for any outreach during the clinical placement with your mentor before making actual plans. Meetings to review your learning and where needed to develop action plans are required at various stages within the duration of the clinical placement. By discussing the dates for these progress meetings in advance with your mentor, you allow them to opportunity to prepare for the meeting and as a result may well have a more productive time. It is a requirement set out by the Nursing Midwifery Council (NMC) that you should work 40% of your time in clinical placement with your mentor therefore a carefully planned off duty is developed for you in order to meet this requirement. If you have off duty requests it is important that these are shared as early as possible for the benefit of your mentor and the other staff.

Be responsible for your own learning Check your signatures |

| Page 29 |

| The main message that I wanted to communicate in this reflection is the importance of being proactive on placement. This is not always easy to maintain when other deadlines are looming, so it is important to keep your mentors up to date with what is happening. This way they can support and guide your learning. An enthusiastic student is more likely to experience a wider range of opportunities while on placement. Put yourself forward for new skills and experiences. Most importantly, take control of your own learning, set objectives that you want to achieve and make the most of your practice area.

Katrina Sealey, Student Nurse at Kingston University |

| Page 30 |

Elective Placement : A Learning Opportunity – Sana Chaudhry. |

| Page 31 |

| My knowledge around certain acute conditions increased, such as understanding and managing pyrexia and various respiratory conditions, the latter was due to high levels of pollution and the dusty atmosphere within Dubai.

The highlight of my experience was working in the paediatrics department. Though I have pursued my journey in the Adult field of nursing, I have a great interest in paediatric nursing. I assisted in giving babies vaccines, nebulizers and measured their weight and height. This reinforced my passion to work with children in the near future. To summarise my experience, it was one of great learning, and working in a multi professional team gave me insight into teamwork dynamics. Having encounters with various service users from different religions and cultural backgrounds allowed me to broaden my knowledge and sensitivity around dealing with people, and meeting their needs accordingly for example, Muslim Arab women wanted to be seen by female as oppose to male nurses and healthcare professionals, due to their religious beliefs, especially when there was a need for a physical examination. The month of fasting, known as Ramadan can pose a few issues both with service users and healthcare professionals. With scorching temperatures and long Summer days, fasting can impede on concentration levels, but this is counter-acted by the traditional afternoon Siesta time workers have. From 13.00 to 16.00, staff go home and rest, and commence their shift afterwards. Despite the hardships people face with regards to fasting, people have encountered tremendous ‘spiritual energy’ and willpower that miraculously pulls them through the 30 days of Ramadan…amazing accomplishment is felt at the end of this holy month. I would highly recommend anyone who has an opportunity to go on an EPLO, to take the opportunity to do so. The learning that takes place out of your comfort zone is reinforced and cemented in your memory for years to come, my personal experience has proved so. Sana Chaudhry, Student Nurse at Kingston University |

| Page 32 |

| Page 33 |

| 8. Conclusion;

9. Up to 5 Key points, highlighting the main issues arising from the study that can inform nursing and health care practice; 10. Up to four boxes, photographs, figures or tables; 11. Up to 4 key words or search terms; 12. Articles should be submitted using Calibri (body), font size 11 and using 1.5 line spacing; 13. References should be in the Harvard style, with the author’s surname first, followed by a comma and the initials of their given or fist name, e.g., Williams, D B. All authors of an article should be included unless there is more than 5, in which case only the first should be used followed by ‘et al’ 14. One author should be used as the correspondent Submission of an article · Contact number · Full postal address · A submission declaration that the work is that of the authors and that it has not been submitted to another source or been used in another publication and subjected to copy right. · Permission has been given for use of copy righted material from other sources, including the internet. · Ensure that your article has been checked for spelling and grammar. · References are in correct format for the Journal. · All references cited in the reference list are cited in the text and vice versa. · The proof reading of your submitted article, and subsequent checks prior to publication, are the sole responsibility of you the author/s. · Please define abbreviations and ensure consistency when using them. · Divide your work into clearly defined sections, results, discussion, conclusions and appendices. |

| Page 34 |

| Final points to Note Authors must agree to our publication policies and remember the Editor’s word is final. Please add a covering letter saying who you are and what your proposed publication is about. Unfortunately we are unable to pay contributors as we are only a small organisation and are looking for enthusiastic committed individuals to support us. Figures and photographs should be of a good enough quality to be included without further work. Remember to consider the readership of the journal and the fact that for many people, English will not be their first language. There is help with the use of English from an editing service at; Elsevier’s Webshop, and other writing services on the net. There are separate guidelines for case studies which can be found on the next page. |

| Page 35 |

| Page 36 |

| Page 37 |

| This poem is written by Sharron Frood from her time working in the South African townships with mamas and orphans. |

| Page 38 |